This piece is also published as a Policy Brief at the Stanford Institute for Economics Policy Research.

In 2021, Congress determined that broadband connectivity in rural areas was poor and not improving quickly enough and created the Broadband, Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program. BEAD earmarked more than $42 billion for states to expand high-speed internet access under the direction of the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA).

In a previous blog post we explained how removing states’ ability to use leftover BEAD funds also removed their incentive to spend the money efficiently. That problem could be lessened through various bidding rules and resolved by allowing states to keep leftover funds. In this post, we discuss a problem inherent to BEAD and any similar infrastructure subsidy program: Winners’ incentive to come back to the government later to ask for more subsidies and inability to credibly claim they won’t. The post-award incentive to return to the trough does not have an easy solution. Consider, for example, the almost inevitable cost-overruns on other large infrastructure projects (looking at you, California high-speed rail) that taxpayers invariably cover.

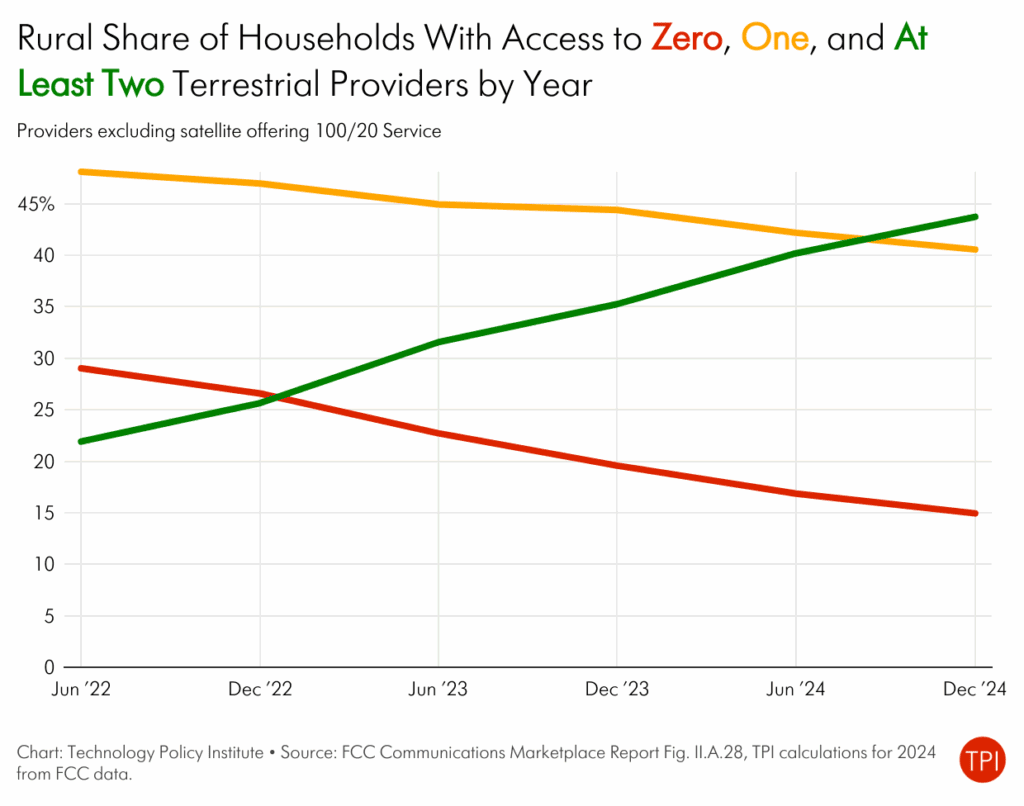

While eliminating this problem is likely impossible, understanding may help NTIA and the states design their bidding processes to reduce the problem. In this post we discuss the extensive economic analysis of the problem and suggest some ways NTIA and the states might mitigate it, at least partially.[1] The ultimate solution in this case is to facilitate broadband competition across the country so that no parties will merit subsidy.[2] Fortunately, competition in rural areas is growing quickly, with the share of rural population lacking terrestrial broadband options falling by half since 2022.

The Post-Award Renegotiation Problem

Nearly 50 years ago, Nobel prize winner Oliver Williamson wrote a seminal paper on the problems involved in soliciting bids for monopoly service in the context of early cable TV franchises.[3] His key point was that the winner becomes a monopolist with strong incentives to renegotiate terms or seek additional government support after winning the contract, particularly if initial bid commitments prove unsustainable.

Because providers can optimize across the BEAD subsidy, expected USF payments, and expected consumer revenues, they may submit unrealistically low bids while planning to seek future USF support, exactly the kind of post-award renegotiation that concerned Williamson.

We already see evidence of this problem. For example, the former director of Washington state’s broadband office wrote,

several BEAD applicants and state broadband offices…seemed hopeful they could skirt these financial realities by banking on ongoing funding from the federal Universal Service Fund (USF). In other words, some applicants whose anticipated revenues can’t cover their anticipated costs expect the federal government to provide perpetual operating subsidies – on top of the initial BEAD construction funds.[4]

The underlying problem of bidders counting on post-auction renegotiation remains unsolved for large, complex infrastructure projects. However, some auction rules can at least partially mitigate the problem. We turn to that analysis in the next sections.

The Monopoly Pricing Paradox

One issue programs like BEAD face is that by definition they create subsidized monopolists, which, all else equal, gives the winner the ability to price like a monopolist. Yet, if winners face price regulation that limits their profits they may be more likely to ask for future subsidies.

Williamson was skeptical that it was possible to overcome this paradox, particularly where the product is complex and technology changing, like broadband. More accurately, he did not believe either the winner or the government could credibly promise to reject renegotiation.

While the challenge of credible, enforceable commitments remains, procurements attempt to mitigate Williamson’s pessimistic view primarily by using scoring mechanisms that account for multiple bid dimensions. In principle, scoring makes it possible to balance proposed quality with proposed prices, and, therefore, the winner’s incentive to renegotiate in the future. Whether this works in practice for complex infrastructure like broadband networks remains an open question.

There is no single best way to put theory into practice. The Biden NTIA arguably put too much emphasis on prices by including a vague “middle class affordability” criterion.[5] That would have encouraged firms to promise overall lower prices which, in the first place, probably were not credible while also giving winners justifications for asking for more subsidies later. That is, they could have argued that the pricing rules made it impossible for them to generate enough cash flow to operate their networks.

The new NTIA rules mostly eliminate that and other price regulations.[6] Providers still must include “at least one LCSO [low-cost service option].” [7] The ability to set prices and have a LCSO restricted to eligible households helps mitigate the network sustainability problem and reduce the validity of post-auction renegotiation arguments, but does not change the incentive for firms to try.

The Satellite Competition Variable

Williamson’s analysis focuses on bidding to become a monopolist. BEAD is premised on the notion that some areas of the country have no broadband service, implying that the winner would become a monopolist, but this premise is true only rhetorically given satellite coverage. Virtually the entire country is now capable of receiving broadband service through satellites, although given current capacity constraints, not everyone in an unserved area can be served simultaneously at speeds that qualify as “broadband.” For that reason and because LEO broadband service is currently more expensive than most terrestrial options, the presence and increasing capacity of LEO satellite broadband may provide some constraint on monopoly pricing.

NTIA instructs states to be technology-neutral as long as the technology meets minimum standards, but the existence of LEO satellite service fundamentally changes the competitive landscape. To generalize and simplify, compared to terrestrial service, LEOs have a low fixed cost to connect a household anywhere and a higher operating (and opportunity) cost to provide service to each household. The fixed cost difference increases as household density decreases, meaning that LEOs will have more of a cost advantage for sparsely populated areas.

Given these economics, a competitive BEAD procurement process will yield one of two competitive situations, each with its own post-award challenges:

The Preexisting Monopoly Problem

Where Starlink is the only broadband option it is by definition a monopolist. When Starlink is the winning bidder, it becomes a subsidized monopolist that, per NTIA’s rules, cannot be subject to rate regulation. Starlink’s national pricing at least in part mitigates the pricing concern. The exception is that the company uses congestion pricing to manage locations where it faces capacity constraints and could, in principle, charge more in areas in which it is a monopolist under the guise of congestion pricing. But if they could do that one would imagine they already are and, to our knowledge, nobody has accused the provider of such behavior. Additionally, winning a BEAD award would not change that incentive. Additionally, as with other providers, the need for a LCSO also helps mitigate some pricing power concerns although, on the other hand, a LCSO that encourages adoption could create congestion.

This situation is similar to the Williamson analysis in that Starlink is a monopolist, but differs in that much of the infrastructure is in place, although more satellites may be necessary depending on demand. It is also different in that Starlink faces the threat of new entry, especially by OneWeb and Amazon’s Kuiper LEO broadband service, and by the expanding footprint of terrestrial fixed wireless broadband.

The Terrestrial Provider Predicament

It is important to know how much Starlink would constrain a subsidized provider’s prices. Starlink is typically more expensive than other options, particularly when taking quality into account. Thus, while monopoly pricing may not be possible in areas where a terrestrial provider wins the BEAD process, competitive pressure may be limited. As a result, while this situation differs from Williamson in that it does not yield a pure monopoly, many of the incentives he discusses remain the same.

Some of the incentives may be even more pronounced than Williamson surmised. In particular, providers may bid knowing they have to compete with Starlink, if not in the auction then in the marketplace. They could later argue that they submitted a low bid under the assumption that they would be a monopolist but then had to compete with Starlink, making their networks financially unsustainable.

The Forced Commitment Paradigm

Williamson’s analysis and the general inability to manage the problems he foresaw for the next 50 years leaves states in an unenviable position. Still, they can design selection processes in ways that reduce future problems. The federal government, meanwhile, can design ways to help enforce commitments, such as capping the size of the Universal Service Fund, particularly the High-Cost Fund thereby making it difficult for additional firms to draw from it.

A key problem Williamson identifies is that bidders cannot credibly promise not to renegotiate the contract after winning. A constraint on the possible outcomes of such a renegotiation could help make promises somewhat more credible. In particular, capping the Universal Service Fund’s High Cost Fund would mean that any money allocated to new networks would have to come from old networks, which is a tradeoff politicians will not want to make.

Fortunately, this constraint already exists. The High Cost Fund is capped at $4.5 billion annually. However, the FCC seems to continue to find additional pots of money that it is able to spend on universal service programs, including RDOF, the Mobility Fund, and the 5G Fund. The FCC should promise not to create a BEAD Sustainability Fund.

Of course, the government would face credibility concerns if it promised not to create new funds given the FCC’s history of finding money for new programs (e.g., RDOF, the Mobility Fund, the 5G Fund). This concern would undermine the constraint’s effectiveness. If bidders expect the FCC to find workarounds, a USF cap won’t discipline their behavior. Nevertheless, explicit commitment to avoiding new BEAD-related funds would be an incremental step towards credibility.

Endgame: Competitors Assemble!

Nobody has yet figured out a bulletproof solution to Williamson’s post-award renegotiation problem, even in theory. It’s not reasonable to expect NTIA or the states to figure out a solution now. States can reduce the reasons a winner might come back later and the federal government can try to make it more difficult to violate promises. But the solution to the problem BEAD aims to solve—broadband access—will come from competition.

With enough competitors providing broadband service, the likelihood that previously subsidized competitors will be successful in lobbying for subsidies themselves is lower. Competition in rural areas is, in fact, growing quickly. In addition to low-latency satellite broadband, which is available essentially everywhere, the share of the population with access to no terrestrial broadband options fell by half from June 2022 to December 2024, the most recent data available, to about 15 percent. Meanwhile, the share of the rural population with access to at least two terrestrial providers doubled, from 22 percent to 44 percent.

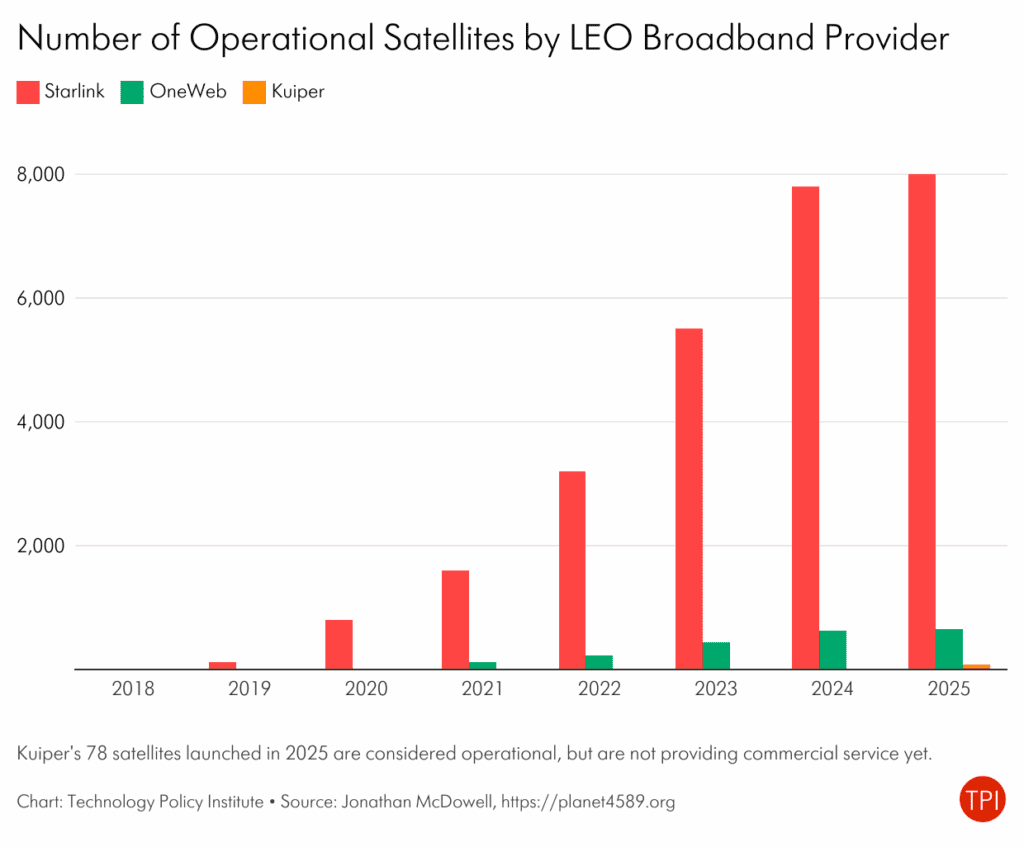

Meanwhile, LEO broadband service is becoming more robust with new competitors entering the market. Starlink is currently the only provider offering low-latency satellite broadband service, but Amazon’s Kuiper has begun launching satellites for its LEO service and other companies, like OneWeb, offer LEO broadband service that currently serves only business customers but could someday offer residential service. Meanwhile, the EU is planning its own system, IRIS2. The figure below shows that Starlink leads in satellite launches, but OneWeb and now Kuiper are launching satellites to start their service as well.

Policy should continue to promote this competition by making spectrum available to help terrestrial and LEO fixed wireless providers, continuing to make it easier to provide service, and also allowing Americans to use friendly countries’ LEO systems once they are operational. States and NTIA should buy time to let competition take hold before winners can come back to the trough.

[1] Giving consumers vouchers (like they do for other government programs) and let providers compete, would be a much better long-term solution to connecting households to broadband than paying providers directly for buildout (and paying them even more for ongoing service subsidies). Despite economists advocating such solutions for a long time, vouchers have not been implemented except for the temporary Affordable Connectivity Program, nor do vouchers seem likely to become a permanent policy any time soon. As a result, we will discuss ways to make the current system somewhat more efficient and better for consumers.

[2] For the purposes of this post, we will not distinguish between “unserved” and “underserved” areas. Also, we note that as with all broadband subsidy programs there are critical mapping questions.

[3] Williamson, O. (1976) “Franchise bidding for natural monopolies in general and with respect to CATV,” The Bell Journal of Economics, Vol 7. No 1.

[4] https://www.lightreading.com/broadband/on-bead-and-rural-broadband-don-t-lose-sight-of-the-goal

[5] NTIA, Notice of Funding Opportunity, Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program (May 12, 2022).

[6] “This notice eliminates the NOFO section titled Affordability and Low-Cost Plans, which includes the requirements for a middle-class affordability plan.” Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program: BEAD Restructuring Policy Notice (June 26, 2025).

[7] “BEAD subgrantees must still comply with the statutory provision to offer at least one LCSO, but NTIA hereby prohibits Eligible Entities from explicitly or implicitly setting the LCSO rate a subgrantee must offer. To be clear, NTIA will only approve Final Proposals that include LCSOs proposed by the subgrantees themselves. Finally, NTIA also hereby modifies the eligible subscriber definition (below) to align it with the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) Lifeline Program and other Federal assistance programs.” Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program: BEAD Restructuring Policy Notice (June 26, 2025).

Gregory Rosston is Director of the Public Policy Program at Stanford University and Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. He is also a Lecturer in Economics and Public Policy at Stanford University where he teaches courses on competition policy and strategy, intellectual property, and writing and rhetoric. Rosston served as Deputy Chief Economist at the Federal Communications Commission working on the implementation of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 and he helped to design and implement the first ever spectrum auctions in the United States. He co-chaired the Economy, Globalization and Trade committee for the Obama campaign and was a member of the Obama transition team. He has served as a consultant to various organizations including the World Bank and the FCC, and as a board member and advisor to high technology, financial, and startup companies. Rosston received his Ph.D. in Economics from Stanford University specializing in the fields of Industrial Organization and Public Finance and his A.B. with Honors in Economics from University of California at Berkeley.

Scott Wallsten is President and Senior Fellow at the Technology Policy Institute and also a senior fellow at the Georgetown Center for Business and Public Policy. He is an economist with expertise in industrial organization and public policy, and his research focuses on competition, regulation, telecommunications, the economics of digitization, and technology policy. He was the economics director for the FCC's National Broadband Plan and has been a lecturer in Stanford University’s public policy program, director of communications policy studies and senior fellow at the Progress & Freedom Foundation, a senior fellow at the AEI – Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies and a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, an economist at The World Bank, a scholar at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, and a staff economist at the U.S. President’s Council of Economic Advisers. He holds a PhD in economics from Stanford University.