Like Jane Curtin and Chevy Chase might have said on Saturday Night Live, with a name like “https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/filings?proceedings_name=17-108” it’s got to be good! That’s the address of the website the public can use to submit comments regarding the Net Neutrality/Title II rulemaking, and they have become almost as controversial as the underlying issue itself. Newsworthy incidents so far include an extended time period when the site was not available; racist comments targeting Indian-American chairman Ajit Pai; comments submitted under false names; and questions of how the agency should interpret millions of comments.

The latter has become particularly relevant in the net neutrality debate given the large number of comments submitted. The 2015 Open Internet Order received 3.7 million comments total, and the current rulemaking has received almost 5 million to date. Counting is easy. Knowing what that count means is not.

For the agency itself the answer is simple. The Administrative Procedure Act (APA) mandates the public have an opportunity to provide input, and the agency must take them into account. However, the agency is supposed to respond to arguments, not to public opinion. Independent expert agencies in particular are not intended or designed to aggregate public preferences and translate them into policy. Thus, one million identical arguments deserve one reply, and the extent of that reply should be a function of the depth of the argument presented, not the number of people or organizations who submit it.

A 2008 Nonpartisan Presidential Task Force Report explained:

…the quantitative level of participation should not be given greater priority than the quality and balance of participation. It is more important that the agency hear from all distinct viewpoints than that it hear from large numbers of individuals or groups expressing the same arguments or conveying the same information.

To paraphrase a common saying, every argument is important, but it is not important that everyone make it. Millions of nearly identical comments are unlikely to offer new insights. The Congressional Research Service noted, “The agency or proponent of the rule has the burden of proof, and such rules must be issued ‘on consideration of the whole record … and supported by … substantial evidence.’” The number of comments received is not likely to be considered “substantial evidence.”

Nevertheless, even if the agency should not be influenced by the number of comments, the existence of large numbers of comments is not meaningless.

To policymakers outside of the rulemaking agency, millions of comments and successful fundraising campaigns may indicate simply that large numbers of people care about an issue. In other words, even though each of the millions of identical comments do not add new arguments to the debate and may not represent popular opinion, collectively they mean the obvious: a significant number of people care enough to have an opinion.

If we accept that a large number of comments indicates that an issue is particularly controversial, and that broad societal preferences should generally be taken into consideration for especially controversial issues that concern large numbers of people, then a logical conclusion is that an expert agency rulemaking may not be the right venue for making the relevant decision.

Instead, the correct institution to resolve the issue is one designed to aggregate society’s preferences and turn them into laws. In particular, Congress, not an expert agency, is intended reflect the will of the people.

It is impossible, of course, to set a non-arbitrary threshold above which an issue should be decided by the legislature rather than an agency. Fortunately, the level of controversy and high number of comments we see in the net neutrality fight are rare.

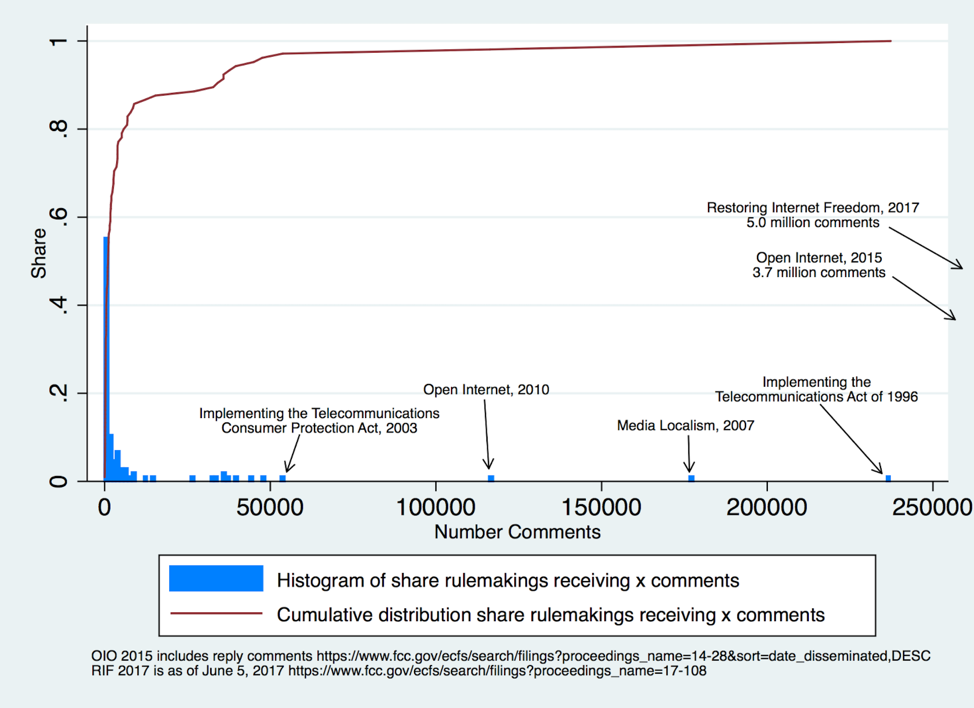

In an earlier paper I collected data on major FCC rulemakings between 1994 and 2013, including the number of comments each received. The figure below shows that even among major rulemakings, the FCC tends to receive a relatively small number of comments.

Distribution of Number of Comments Received in Major FCC Rulemakings

Only a small number of rulemakings receive more than a few thousand replies. The Open Internet proceeding of 2010 was an outlier and received about 116,000 comments. The 2015 net neutrality / Title II proceeding received about 2.2 million comments (not including replies) while the current proposed rule has received about 5 million comments thus far.

Additionally, in the case of net neutrality—and perhaps in the case of any similarly controversial issue—the agency’s rules are likely to continue to be reversed with each change in party control. Legislation is more difficult to enact than rules, but also more difficult to change once passed. Thus, another related argument in favor of moving the decision to Congress is to create a (more) stable outcome.

Reality, however, does not necessarily follow logic. Despite the rhetoric, few in DC have much incentive to want the issue to go away. Millions of comments to the FCC also represent millions of fundraising opportunities. Groups arguing all sides of the issue financially benefit from the ongoing argument.[1] Congress, meanwhile, probably will not weigh in before the 2018 election regardless of what the FCC does because that would mean giving up a campaign issue likely to be lucrative to members on both sides of the aisle.

Free Press Net Neutrality Fundraising Ad

Thus, in the end, I suspect that millions of comments mostly mean that even after the current rulemaking is resolved, we will be stuck with this issue at least until sometime after the 2018 election and probably longer. Setting aside politics, it still remains the case that if the issue is to take into account broader public opinion then Congress is the only institution that can resolve it and, regardless of broad interest, only legislation has a chance of leading to a stable solution. Then, we can all finally move on to something else.

[1] I am not entirely lacking in self-awareness. I know this must be true also for the Technology Policy Institute. However, I’d like to believe that my extreme irritation with thinking about net neutrality for more than a decade and therefore desire to see it banished to the dustbin of history exceeds my desire to raise money. Then again, as Tyrion Lannister said, “most men would rather deny a hard truth than face it.”