California’s state legislature is considering a bill that would require social media companies to pay a fee for the news articles that are shared on their platforms. Meta has said that if the bill passes, it will block news-sharing capabilities in California.

The bill’s supporters argue that revenues from the tax would benefit struggling news publishers.

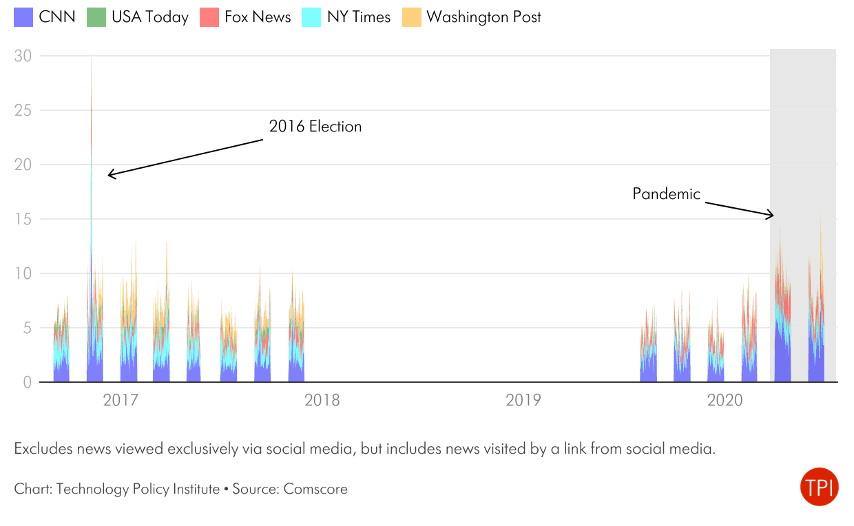

As with any proposed legislation, its expected net benefits should be positive, but legislators do not appear to have considered all the costs. TPI’s study, “Where Does the Time Go? Competing for Attention in the Online Economy,” authored by scholars Scott Wallsten, Sarah Oh Lam, and Nathaniel Lovin, highlights a potential cost of the bill: site traffic. Controlling for factors affecting causality, the research found that for every minute an individual spends on social media, they spend an additional 0.12 minutes on news. For every minute spent on news, a user spends an additional 18 minutes on social media.

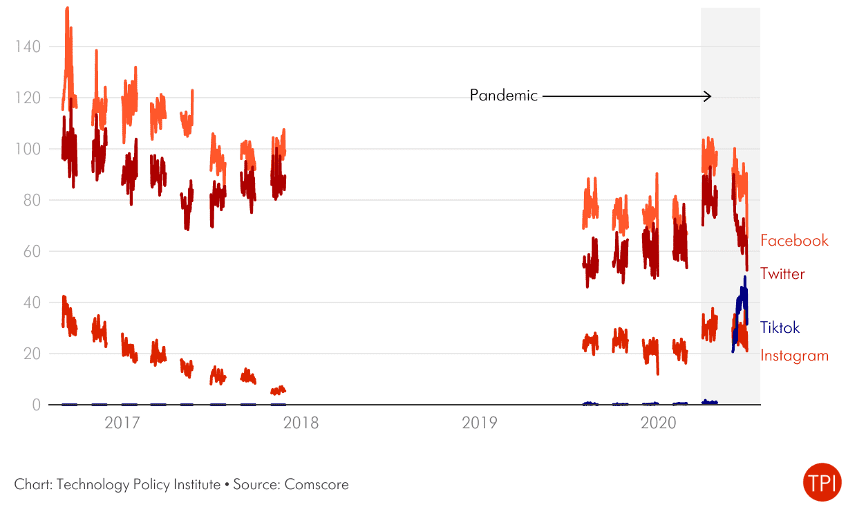

In other words, social media and news are complements: the more time someone spends on social media, the more time they spend on news, and vice versa. California’s bill could interfere with this cycle.

Even if Meta and other social media companies do not pull news altogether, imposing a tax will naturally cause them to reduce the amount of news on their sites. Less news on social media means less time spent on news sites themselves. In either scenario, both news and social media lose site traffic.

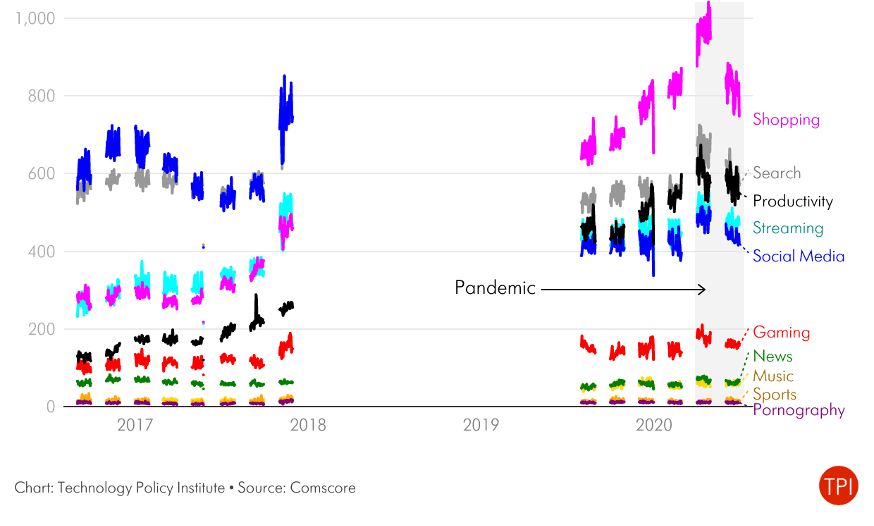

TPI’s research leveraged data on household internet use to investigate the allocation of online time. The paper evaluates online activity as part of an “attention economy,” in which users’ attention is the relevant currency. It approaches the traditional paradigms used to evaluate competition through the lens of time rather than dollars, an economic framework which has implications for organizations that rely on free or fixed price subscription-based content models, as Meta, newsrooms, and streaming platforms do.

In addition to highlighting ways in which different areas of the attention economy affect each other, the paper informs policy making on issues such as mergers and antitrust. How should policymakers approach antitrust and competition policy in a digital, low-price space? With only 24 hours in a day, competition for time is a zero-sum game. While time spent on one activity is necessarily not being spent on another activity, some activities are complements (time spent on activity A correlates with increased time spent on activity B) and some are substitutes (time spent on activity A correlates with decreased time spent on activity B).

Given this interwoven nature, policymakers must be mindful that regulation affecting one part of the attention economy will spill over onto its other sectors. TPI’s research predicts where and how these impacts will manifest.

California legislators are assuming that social media and news compete, and that news is losing. While the crises facing newsroom viability across the country are real, TPI’s analysis reveals that California may be taking a counterproductive route to addressing them. Digital market dynamics must be examined holistically; after all, in the attention economy, money isn’t everything– time is. Rather than taking away from it, time spent on news increases time spent on social media. As such, California’s legislature might help news and social media reap benefits in the attention economy by seeking ways to reduce barriers to content, instead of serving media companies a tax.

TPI’s research puts a price on internet users’ attention. It also helps legislators make policy for online markets. Albeit complex, it is critical that policymakers understand the dynamics between different online activities so as to avoid counterproductive lawmaking, advance consumer welfare, and encourage sustainable economic outcomes.

Not all online platforms are symbiotic, of course, given the finite nature of time in a day. Wallsten, Oh, and Lovin found that streaming and social media are substitutes, meaning that use of one correlates with decreased use of the other.

The paper revealed many other relationships, as well. Time spent shopping and working appear to have a robust positive correlation. In other words, people tend to shop as they work.

The full paper can be found here.

Scott Wallsten is President and Senior Fellow at the Technology Policy Institute and also a senior fellow at the Georgetown Center for Business and Public Policy. He is an economist with expertise in industrial organization and public policy, and his research focuses on competition, regulation, telecommunications, the economics of digitization, and technology policy. He was the economics director for the FCC's National Broadband Plan and has been a lecturer in Stanford University’s public policy program, director of communications policy studies and senior fellow at the Progress & Freedom Foundation, a senior fellow at the AEI – Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies and a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, an economist at The World Bank, a scholar at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, and a staff economist at the U.S. President’s Council of Economic Advisers. He holds a PhD in economics from Stanford University.