The COVID-19 pandemic has put internet access front and center in our lives. Amidst myriad failing public institutions, broadband networks are a rare example of something that’s working well, even under surging demand. It’s not all good news, though. The pandemic has highlighted gaps in coverage and adoption, creating additional hardships for those who can least afford them. Some argue that the importance of broadband and the gaps in usage prove we should consider broadband a public utility like electricity, water, and gas, and regulated as such. These calls join recent, pre-pandemic articles arguing that broadband must be treated as a utility, with electricity typically the utility mentioned. The gist of the argument seems to be that everyone is connected to the electricity grid, electricity is a regulated utility, and therefore broadband should also be a utility.

Electricity and broadband might both be considered “general purpose technologies” in that they both had major implications across the economy. They both are delivered by wires – even wireless broadband requires a connection to cables at some point. Both have publicly owned and privately owned providers. Both are primarily privately owned. Electricity, however, is subject to far more regulation than is broadband. Electricity prices and investments are regulated, while broadband’s are not. Electric utilities, particularly distribution networks, are nearly always monopolies while nearly all households have at least two wired broadband providers and three wireless broadband providers.

Comparing electricity to broadband shows why regulating internet access like a utility would be a mistake. Electric utilities, on average, have not innovated as well as broadband networks. Prices have increased faster, innovation has been slower, and productivity has increased more slowly in electricity than broadband. Additionally, while rural electrification is rightly considered an American success story of the first half of the twentieth century, households adopted electricity more slowly than broadband.

Prices

Prices are notoriously difficult to measure. They can vary across many dimensions making comparisons within an industry difficult, while the quality of the product can change over time, making comparisons over time difficult. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) puts enormous effort into creating price indices that address these problems, enabling comparisons across industries and over time. The most recognized index is the Consumer Price Index, which measures prices of a basket of goods and is the main overall inflation measure.

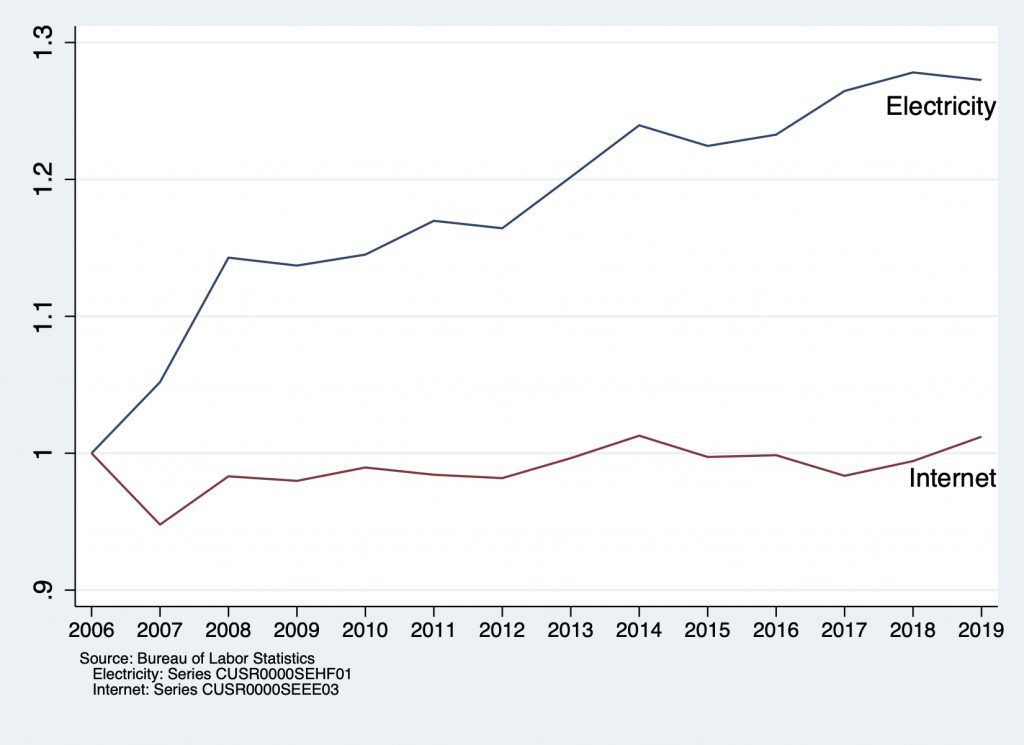

The BLS also calculates quality-adjusted price indices for a wide range of industries, including electricity and internet access. Figure 1 shows these two price indices, both indexed to 1 at 2006. The figure shows that while electricity prices have increased by about 25 percent since 2006, internet access prices have not increased much at all.

Figure 1: Electricity and Internet Price Indices (2006=1)

The point here is not to say what prices should be, or that the price of electricity has increased too much. After all, one might argue that electricity produced with certain fossil fuels like coal should cost even more to account for pollution externalities. Instead, the point is that the history of prices in these two sectors does not suggest that consumers would be better off in terms of cost of living under an electric utility model. To the contrary, BLS data show that electricity prices increased faster than broadband prices.

Data on labor productivity and innovation help explain this price phenomenon.

Productivity

One of the biggest puzzles in economics is what explains the productivity slowdown of the past decade. Productivity growth is crucial because it is fundamental to overall economic growth. Regulated utilities like electricity have exhibited weak productivity growth. McKinsey noted in 2018 that the utilities “sector stands out as having the most consistent decline in productivity growth across countries” (although they are optimistic that technological improvements will eventually improve productivity growth).

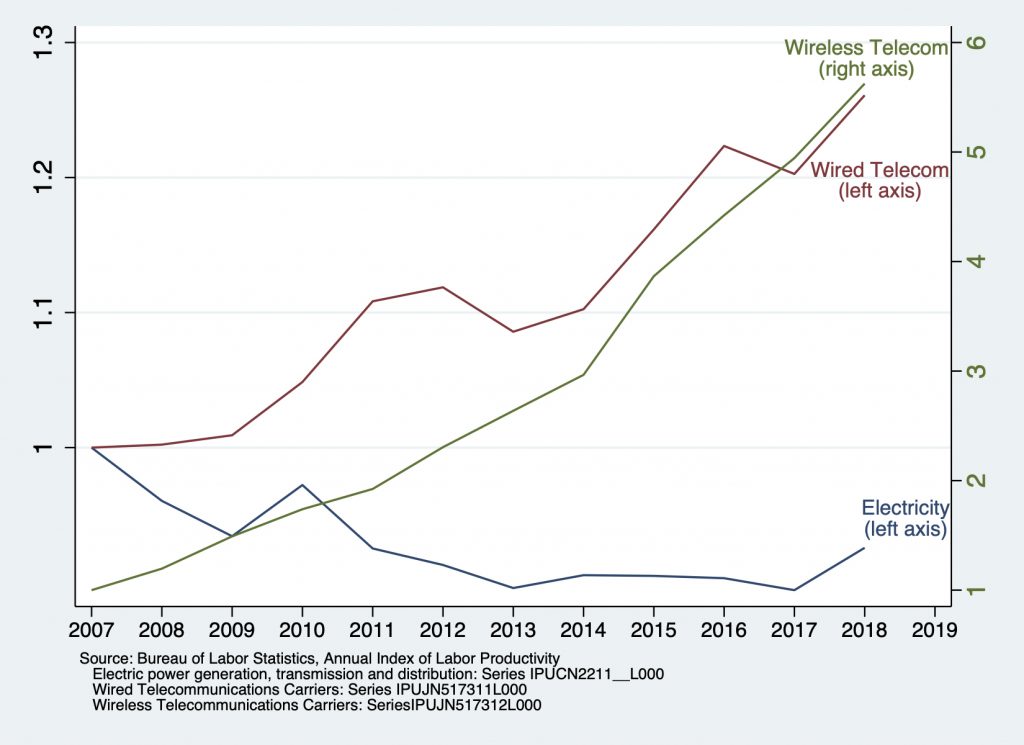

BLS also tracks productivity growth by industry, including electric power generation, transmission, and distribution (NAICS 2211), wired telecommunications carriers (NAICS 517311), and wireless telecommunications carriers (NAICS 517312). Figure 2 shows changes in labor productivity for these three sectors, all indexed to one in 2007.

Figure 2: Labor Productivity Changes in Electricity and Telecommunications Carriers (2007=1)

The figure shows no productivity growth among electric utilities from 2007-2019, consistent with the McKinsey report. To the contrary, productivity in the electricity sector decreased over that time period. By contrast, wired carrier productivity increased by about 25 percent and wireless carrier productivity increased by more than five times.

Innovation

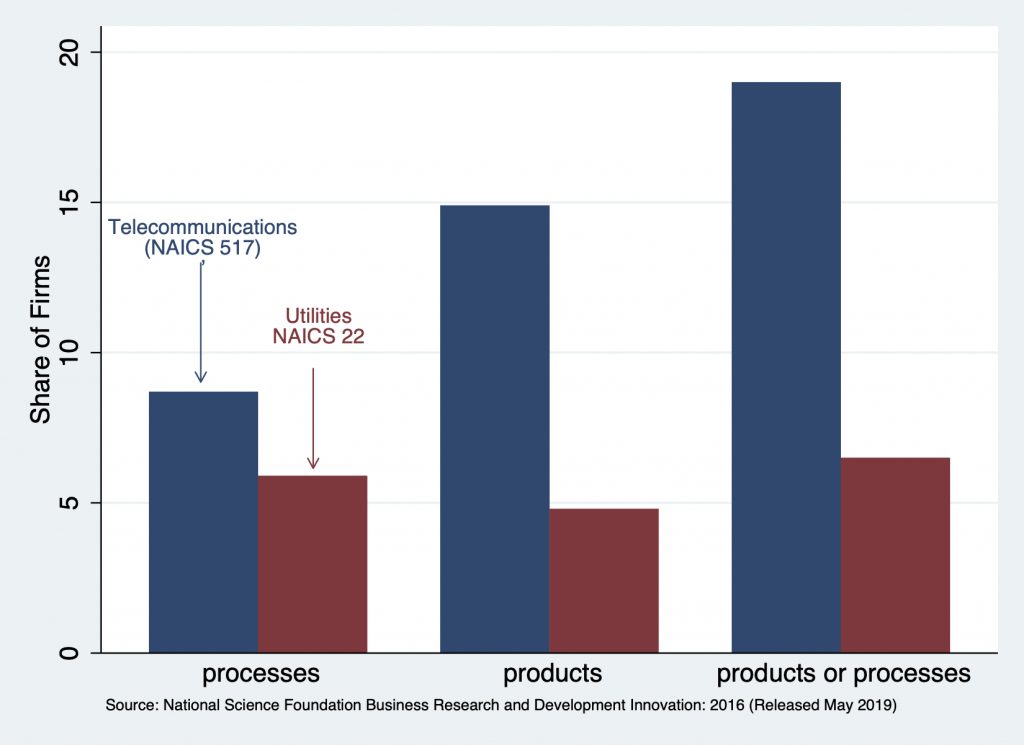

Measuring innovation can make measuring prices look like a cakewalk. Statistics like R&D spending and patent applications, for example, are probably better thought of as inputs into the innovation process rather than representing actual innovation. To address this issue, in 2016 the National Science Foundation (NSF) began asking companies specifically about new products and processes they introduced. Figure 3 shows the share of firms classified as utilities (NAICS 22) and telecommunications (NAICS 517) introducing “significantly” improved products or processes in 2016.

Figure 3: Share of Utility and Telecommunications Companies Introducing “Significantly” Improved Products and Processes, 2016

The figure shows that far more firms classified as telecommunications introduced new products or services than utilities have.

Electrification and Broadbandification

Rapid electrification of the United States, including rural areas, in the first half of the 20th century is rightly regarded as a major success. Some who advocate a utility model for broadband likely have this success in mind when calling for broadband to be treated like a public utility. But the country did not adopt electricity faster than it has adopted internet and broadband, as Figure 4 shows. It took about 25 years to go from ten percent to 70 percent electricity adoption and 15 years to make that same jump for broadband.

Figure 4: Electricity and Internet Adoption

Of course, electricity made it to one hundred percent of households by around 1957. We would have to wait another 30 years or so to see if broadband can fully match the pace of electricity adoption. The challenge we face is to push adoption and availability up to match or exceed electricity’s track record by a lot.

Measuring broadband adoption is becoming increasingly difficult. Mobile and fixed broadband are becoming increasingly good—but not yet perfect—substitutes. The Pew Research Center found in 2019 that 37 percent of Americans “mostly” use a smartphone for internet access at home and 17 percent have only smartphone access, rather than home-based broadband access. Forty five percent of those with only a smartphone say that one reason they did not subscribe to home broadband was that the mobile connection did everything they needed.

For broadband adoption, the question is how to get the remainder of the population online. As has been discussed elsewhere, the remaining digital divide results from a combination of people who do not subscribe where broadband is available and people who do not subscribe because they live in areas where terrestrial broadband is not available.

Some argue that the Rural Electrification Act of 1936, could provide a roadmap to improving rural broadband availability as it did for rural electrification. A detailed comparison of today’s Universal Service Fund that subsidizes broadband in rural areas to the Rural Electrification Agency’s loans is beyond the scope of this discussion, but could be informative. For example, the REA was authorized to finance “the furnishing of electric energy only to persons in rural areas who are not receiving central station service.” Regardless, rural electrification was not faster than rural broadbandification, as it took about 20 years for REA to finish connecting all American farms to the electric grid.

Conclusion

Public utilities such as electricity operate under detailed rate, investment, and operation regulation. Broadband networks do not. Those who call for broadband to be treated as public utilities generally believe that regulation is the means of making terrestrial broadband available to more people. Broadbandification is a goal many share. Treating broadband as a public utility, however, would not change underlying cost structures or the challenges of reaching those who do not have access, nor would it magically provide new capital that could be invested efficiently in extremely high-cost areas.

Prior to the breakup of AT&T, much of our telecommunications network was more or less treated like a public utility. Prices were regulated and the company was required to cross-subsidize service in high cost areas by charging higher prices in urban areas. Such an arrangement is possible only when a monopoly provides service, which is why introducing competition was combined with creating the Universal Service Fund (USF). The USF was intended to provide the funding that was no longer possible in a competitive environment.

The right discussion, then, is about how to improve the USF and the Department of Agriculture’s Rural Utilities Service, which spend more than $5 billion per year in rural areas, yet has left much of it without coverage. The FCC is making progress on increasing the effectiveness of subsidies with its use of reverse auctions to award subsidies. The more spending we can distribute via subsidy auctions the more effective the programs are likely to be.

Calling broadband a public utility seems like a nifty way of solving last-mile access problems. But experience with actual public utilities should give anybody pause before advocating that approach. Electricity prices have increased more than broadband prices, innovation in electricity has been slower, and productivity growth lower. To top it off, electricity was not brought to the country faster than broadband has been.

We need solutions to filling gaps in broadband coverage. Treating broadband the way we treat public utilities is not one of them.