Data privacy is a big issue. Europe’s GDPR and California’s CCPA are perhaps the two best-known privacy laws, but the list of jurisdictions with or considering privacy rules is growing fast. Governments give a variety of reasons for enacting such laws, but one key question is what citizens themselves want.

Recently, we embarked on one of the most expansive endeavors to measure privacy preferences to date, collecting measures for thousands of people across six countries. A full discussion of our analyses is in a recently published article. However, in our experience discussing our results at conferences, we have found that our consistent findings across countries regarding basic demographic groups always receive the most interest for the conventional wisdoms that they do and do not confirm.

In short, we find that around the world,

- Women tend to value data privacy more than men;

- Older people value data privacy far more than younger people; and

- Lower-income and higher-income people tend to value privacy similarly.

Research Method

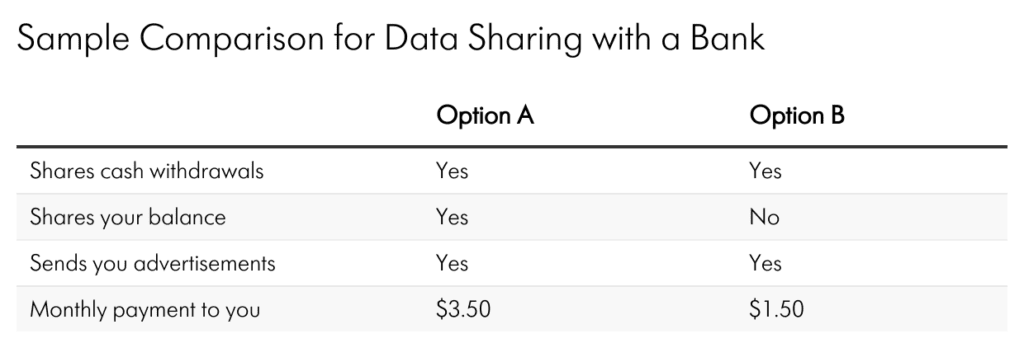

We collected and analyzed data from four separate surveys we designed that employ repeated discrete choice experiments (DCEs). The surveys pertain to respondents’ wireless carrier, Facebook use, checking account at a bank, and smartphone. Each survey asks respondents to make choices among data sharing options that vary according to which data are shared and monthly payments that the respondents would receive. For example, a respondent may be asked to compare the following two options in terms of data sharing (and advertising) with their bank:

Here, sharing of a data type means sharing with third parties. DCE choices like these mimic typical choices in the marketplace (comparisons of features and payments) and have been shown to be capable of eliciting respondents’ tradeoffs. Importantly, unlike more common surveys that people are familiar with, they never directly ask about the issue in question, making it more difficult for respondents to “game” the survey or provide answers that do not match their actual preferences.

To see how it works, consider our example. Choosing Option A implies a monthly payment of $2.00 more than Option B is enough for the respondent to be willing to share bank balance information, whereas choosing Option B implies the $2.00 monthly payment is not enough. By observing many choices with many combinations of data sharing, advertising and payment features, the researcher can pin down privacy preferences quite precisely.

We administered tens of thousands of such (optimally constructed) choices to thousands of respondents across six countries (United States, Mexico, Germany, Colombia, Argentina, and Brazil). The choices made by our respondents allow us to determine what are the data types they want kept private the most, and we can also determine relative preferences for privacy for each data type across demographic groups. The charts below show the average willingness-to-accept for each data type across multiple demographic cuts of our data. The relative size of the bars indicates the relative strength of privacy preferences for each data type.

Privacy Valuation by Demographics (Monthly WTA)

The figures show that women value privacy around twice as much as men. People over 45 value privacy about four times as much as those under 45. However, for income, we see no consistent difference. The only data type where a difference in privacy value by income even appears mildly apparent concerns the sharing of one’s bank balance – a data type where income, per se, plausibly impacts the value of its privacy.

The comparisons in the figure are averaged across all six surveys. However, they generally hold even if one looks at each country individually. Hence, this appears to be a pattern that persists across many international borders. In a recent working paper looking at another group of seven countries (the only overlap being the U.S.), we again find this general pattern.

What can we do with such findings? If just taken at face value, we can see where support – and opposition – to privacy protection measures are likely to lie in the populus. Understanding variation in preferences can also help guide a two-way dialogue. Are those who place less value on privacy more attuned to benefits from the sharing and utilization of their data? Or are they less aware of the risks that come with their data being “out in the wild?” Are there characteristics related to age and sex, but not income, that drive one’s privacy preferences?

Taking steps toward understanding and addressing privacy preferences is important for good policy. To the extent that the public are not fully informed of risks and benefits of data sharing, there can be benefits from engagement by knowledgeable experts. On the flip side, experts and policymakers may also benefit from tools and analyses designed to gather and summarize the diffuse “wisdom of the crowd.” Studies like ours can help experts understand where their expertise may be best shared and also where there may be gaps in their understanding.