Another day, another dozen political texts.

Campaigns know we’re numb to the endless television, radio, and online ads that arrive like a tsunami as election day approaches. So they looked elsewhere and found their holy grail: Texts.

We open something like 98% of all texts we receive. That’s an irresistible target. Texts are the most intimate platform there is. But that’s where we want to hear from family and friends, not politicians’ thoughts about how America is “on the precipice.”

That’s just spam.

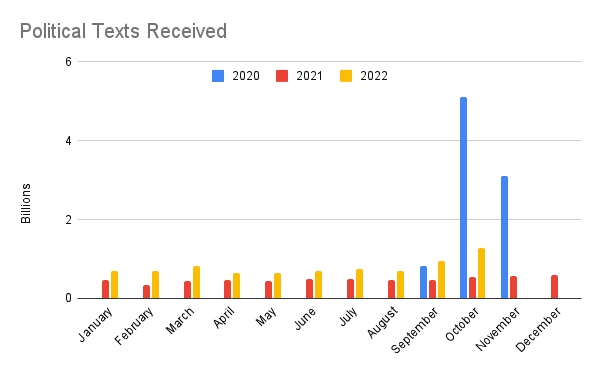

Robokiller reported about 11.6 billion political texts in the last three months of the 2020 campaign, and about 5.8 billion in 2021. (Republicans sent about 87% of them. Do with that information what you will.) We’re up to almost 8 billion through October of this year.

Ironically, the government understands that other spam texts are a nuisance. The Federal Communications Commission has cracked down on unwanted messages and are engaged in a process to better target “illegal texts.”

But texts that would be illegal if sent by a commercial entity are legal when sent by campaigns.

Political texts are governed by the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA), which prohibits auto-text systems, but, unlike commercial texts, does not require consumers to opt-in to receive political texts. Political campaigns exploit that difference and loopholes created by ambiguous wording to keep those texts rolling. The FCC’s current rulemaking, unfortunately, focuses on illegal–that is, not political–texts only.

Dealing with this issue is hard for at least two reasons.

First, as annoying as these texts are, laws or regulations governing political speech move into tricky territory: How can we ensure that incumbent politicians–regardless of who they are–will create rules that are fair to challengers? Additionally, it’s important, particularly given the uniquely American apathy about voting, that candidates have ways of reaching citizens to explain positions and encourage them to vote. My guess, though, is that texts successfully raise money, since campaigns can immediately measure that, but have little, if any effect on voter participation or desire to vote for the candidate sending end of the text.

Second, politicians do not like anyone interfering with their money vacuums and could make life difficult for those who try. Last year, political and advocacy groups were infuriated by so-called “10DLC” rules created by carriers, which are essentially a set of rules that campaigns must follow to ensure their mass texts are delivered. The head of the Democratic National Committee argued that blocking texts “…is nothing less than the silencing of core political speech at the hands of a private company pursuant to an ambiguous, unwritten policy.”

Nevertheless, both parties scrambled to find ways to comply with the rules. It’s too early to know for sure, but these rules may actually be having some success. In August, September, and October of 2020 cell phone owners received about 9 billion political texts. In those same months of 2022 the number was about 3 billion. To be sure, 2020 was a presidential campaign and 2022 is an off-year election, so we would expect less activity.

That doesn’t mean only the private sector can help clean up this mess. The FCC may be able to do a few things, like closing loopholes. Having a human press “send” as the trigger to release thousands of emails into the ether obviously violates the spirit of the TCPA. But no rules are free of loopholes, and if there’s money to be raised, organizations will find and exploit them. The TCPA rules have been revised several times since they were passed in 1991 to close loopholes and take into account new technology.

In the short run, it’s up to us to try to ward off the flood. If a politician texts you, reply with STOP or NO or I DON’T EVER WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU AGAIN. Or engage in another national pastime: complain about it on social media, and name the offending campaign. It’s satisfying, and it might remove you from whatever list they used to contact you.

Then delete the thread and maybe change your number.