For consumers, 2012 was a great year in wireless. Carriers rolled out 4G networks in earnest and smartphone competition heated up. Apple’s iPhone 5 release was no surprise. But no longer was Android relegated primarily to low-end phones. Ice Cream Sandwich received strong reviews and Samsung launched high end Android devices like the Galaxy S3 that rivaled the iPhone. Microsoft kept plugging away at the margins and introduced Windows Phone 8 with a new partner in Nokia, which had seen better days. For its part, RIM provided investors with numerous opportunities to short its stock.

I love gadgets. Especially new gadgets. So I eagerly awaited the day my wireless contract expired so I could participate in the ritual biennial changing of the phone. (I wish I could change it more frequently, but I wait to qualify for a subsidized upgrade because we also have to do things like occasionally buy food for the kids). But what phone to choose?

The iPhone 5 was mostly well-received, and even early skeptics like Farhad Manjoo wrote that once you held it you realized how awesome it was. Still, even though it had become a cliche critique, to me it just looked like a taller iPhone, not a newer iPhone, and I wanted to get something that felt really new, not really tall. Am I a little shallow for rejecting an upgrade for that reason? Yes, yes I am.

So after reading rave reviews and talking to friends who had already upgraded, I got the Samsung Galaxy S3.

The Android lock screen customizations and widgets should have made me happy, but they didn’t. I couldn’t find a setup I liked. The Samsung’s hardware didn’t work for me. Buttons on both the right and on the left sides of the phone meant that every time I tried to press the button on the right I would also press the button on the left, screwing up whatever important task I was doing (OK, maybe that “important task” was Angry Birds, but still). Those aren’t inherent criticisms of Android or the Galaxy S3. They’re just my own quirks. (It isn’t you, it’s me).

Finally I got so frustrated with my phone that one day I hopped off the Metro on my way to work, went to the nearest AT&T store, returned it, and re-activated my old iPhone 4.

My first reaction to reanimating my 4 was relief that I could once again operate the phone properly. My second reaction was, “holy **** this screen is tiny!” I was sure my iPhone 4 had turned itself into a Nano out of spite while languishing unused.

After that, the Nokia Lumia 920 with Windows Phone 8 caught my eye. Great reviews (including this thoughtful and thorough review by a self-professed “iPhone-loving Apple fangirl” at Mashable who switched to the Lumia for two weeks), beautiful phone. And those “Live Tiles” on the home screen! No more old-fashioned grid-style icons. This, finally, was something new.

After that, the Nokia Lumia 920 with Windows Phone 8 caught my eye. Great reviews (including this thoughtful and thorough review by a self-professed “iPhone-loving Apple fangirl” at Mashable who switched to the Lumia for two weeks), beautiful phone. And those “Live Tiles” on the home screen! No more old-fashioned grid-style icons. This, finally, was something new.

I wanted to love it. I tried to love it. I brought it home to meet my family. Some features are wonderful. The People Hub, in particular, combines Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn feeds in a nicely readable format. Nokia helped by developing a suite of apps for it and making great hardware. The phone is a nice size, has an excellent camera and a two-LED flash (which makes it the most versatile, if not the most powerful, $450 flashlight on the market). And while some reviews have complained about its heft, I appreciate a phone that can be used for self-defense.

But at the end of the day — and after the return period, natch — I just couldn’t handle being on the wrong side of the network effects.

Network Effects

Network effects come in two flavors: direct and indirect. With direct network effects, every user benefits as other users adopt the technology. Old-fashioned voice telephones are the classic example. If you own the only phone it is worthless because you can’t call anybody. But when the next person buys a phone you immediately benefit because now you can call him or her. (Unless you can’t stand that person, in which case his phone reduces the value of your phone to you, especially since with only two phones in the world it’s not like you can just change your number).

Direct network effects aren’t a big issue with smartphones for most people. You can call any number from any device. (Though for curmudgeons like me that’s increasingly a cost rather than a benefit. Why am I expected to drop everything I’m doing and answer the phone just because someone else decided it was time to chat?) Popular apps like Facebook and Twitter, whose value derives from the size of their networks, are platform-agnostic, at least with respect to hardware and operating systems, so each user gets the benefit of additional users regardless of the (hardware and OS) platform.[1]

But, like The Force, indirect network effects are all-powerful among mobile operating systems. To paraphrase Obi-Wan Kenobi, “…indirect network effects are what give a smartphone its power….They surround us and penetrate us; they bind the users and app developers together.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x2YQJsbbWNA

In other words, because the vast majority of all potential customers are on iOS or Android devices, it makes sense for developers to build apps for those platforms. If apps are successful there, then maybe it’s worth building apps for a small platform like Windows Phone. Those general incentives are true whether you are the proverbial kid in the garage or Google.

These incentives apparently even affect developers at Microsoft. While Microsoft seems to be putting significant resources into the Windows Phone operating system, it’s not clear that other Microsoft developers share the love. For example, although Microsoft owns Skype, the Windows Phone 8 Skype app was not available when the first phones went on sale. Skype is still only a “preview” app in the Windows Phone store.

These incentives apparently even affect developers at Microsoft. While Microsoft seems to be putting significant resources into the Windows Phone operating system, it’s not clear that other Microsoft developers share the love. For example, although Microsoft owns Skype, the Windows Phone 8 Skype app was not available when the first phones went on sale. Skype is still only a “preview” app in the Windows Phone store.

As a result, Windows Phone users get the short end of the app stick.

To be sure, the Windows Phone store is far from empty, and some people will find everything they need. Certain apps I rely on, like Evernote and Expensify, are there and work well.

But, overall, the Windows Phone store feels like a dollar store. It has a lot of stuff–75,000 new apps added in 2012, according to Microsoft–but when you look closely you realize they’re selling Sherple pens rather than Sharpie pens. Sometimes the Sherple pen works fine. For example, Microsoft promised to deliver a Pandora app sometime in 2013, but in the meantime users can rely on the “MetroRadio” app, which somehow manages to play Pandora stations. God bless those third-party developers for stepping in and making popular services available to those of us who who love them so much we’re willing to pay any price, as long as the price is zero. But third-party apps can stop working anytime the original source changes something, and it feels like being a second class citizen in the app world.

Small platforms also have problems at the high and low end of the app ecosystem. Windows Phone is missing certain hugely popular apps like Instagram. At the same time, because of the small customer base the odds of this month’s hot new app being readily available on (or much less, originating on) Windows Phone are tiny.

Relying on a competitor can be OK if you have some power

Even worse, not only does Microsoft need to overcome its network effects disadvantage in order to succeed, it must also have good access to products developed by its arch-nemesis, Google.

Relying on a competitor isn’t inherently disastrous. Apple clearly benefits from the excellent products Google makes for iOS. Recent stories have even suggested that some of Google’s iOS products are better than its companion Android products. There is no love lost between Google and Apple, but Google apparently needs Apple’s huge customer base as much as Apple needs Google.

That’s not to say such cooperation is easy or without risk. Apple buys chips for its mobile devices from archrival Samsung, but has become wary of relying on a competitor for such a crucial part of its golden goose. Similarly, Netflix relies on Amazon’s AWS data facilities for its video streaming, even though they compete in the video delivery market. That relationship, too, makes some uneasy, for example, when Netflix service went down over Christmas and Amazon’s did not. Nevertheless, Amazon and Netflix apparently believe each has enough to gain by working with the other that the relationship continues despite such hiccups.

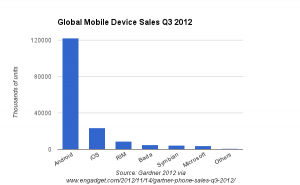

But with only about two percent of the market, Microsoft is but a fart in a mobile windstorm. Even if Windows Phone were not a potential competitor to Android, it’s hard to make a business case for Google to care one whit about Windows Phone today. That is, Google faces the same lack of incentive to develop apps for Windows Phone that all developers face. And, given that Windows Phone is trying to compete with Android, it’s hard to come up with a good reason why Google should invest in the Windows Phone platform. In other words, Microsoft needs Google but Google doesn’t need Microsoft.

But with only about two percent of the market, Microsoft is but a fart in a mobile windstorm. Even if Windows Phone were not a potential competitor to Android, it’s hard to make a business case for Google to care one whit about Windows Phone today. That is, Google faces the same lack of incentive to develop apps for Windows Phone that all developers face. And, given that Windows Phone is trying to compete with Android, it’s hard to come up with a good reason why Google should invest in the Windows Phone platform. In other words, Microsoft needs Google but Google doesn’t need Microsoft.

And Google’s lack of need for Windows Phone shows. YouTube doesn’t work well on Windows Phone, gMail on the Windows Phone web browser looks like it was designed for an old feature phone, and Google itself offers only one, lonely, app–a basic search app–in the Windows app store.[2]

This isn’t anti-competitive behavior by Google by a long shot. The small number of Windows Phone users means that Google is unlikely to earn much of a return on investments in Windows Phone. And given that those returns are likely to be even lower if the investments help the Windows platform succeed, it becomes difficult, indeed, to see a reason for Google to invest much. If Windows Phone acquires enough users to generate sufficient ad revenues, however, you can bet Google will develop apps for it.

A New Hope

A third mobile platform could still succeed, despite these obstacles. Overcoming them will require enormous resources, and Microsoft, with an estimated $66 billion in cash, clearly has them. Whether it will deploy those resources effectively remains to be seen. IMO, more resources developing apps and fewer on embarrassingly bad ads might be an effective approach.

Like I said, I wanted to love my Lumia 920. And I want this new platform to succeed–more competition is good. I just don’t want to see it enough to suffer on the wrong side of the network effects in the meantime.

My iPhone 5 comes tomorrow. Don’t tell my wife I used her upgrade.

____________

[1]There are exceptions, of course. For example, Apple’s FaceTime and Find Friends app work only on Apple devices, but–much to Apple’s dismay, I’m sure–these do not appear to have had much effect on aggregate sales, at least in part because of close cross-platform substitutes like Skype and Google Latitude.

[2]Again, some third-party developers come partly to the rescue. Gmaps Pro, for example, provides a wonderful Google Maps experience on Windows Phones.

Scott Wallsten is President and Senior Fellow at the Technology Policy Institute and also a senior fellow at the Georgetown Center for Business and Public Policy. He is an economist with expertise in industrial organization and public policy, and his research focuses on competition, regulation, telecommunications, the economics of digitization, and technology policy. He was the economics director for the FCC's National Broadband Plan and has been a lecturer in Stanford University’s public policy program, director of communications policy studies and senior fellow at the Progress & Freedom Foundation, a senior fellow at the AEI – Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies and a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, an economist at The World Bank, a scholar at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, and a staff economist at the U.S. President’s Council of Economic Advisers. He holds a PhD in economics from Stanford University.