Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick’s National Telecommunications Information Agency (NTIA) is trying to make the $42 billion Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program more efficient. We applaud its focus on deployment to unserved areas, cost, and technological neutrality. However, at least one new provision threatens to undercut these efficiency incentives.

To understand how, consider a thought experiment.

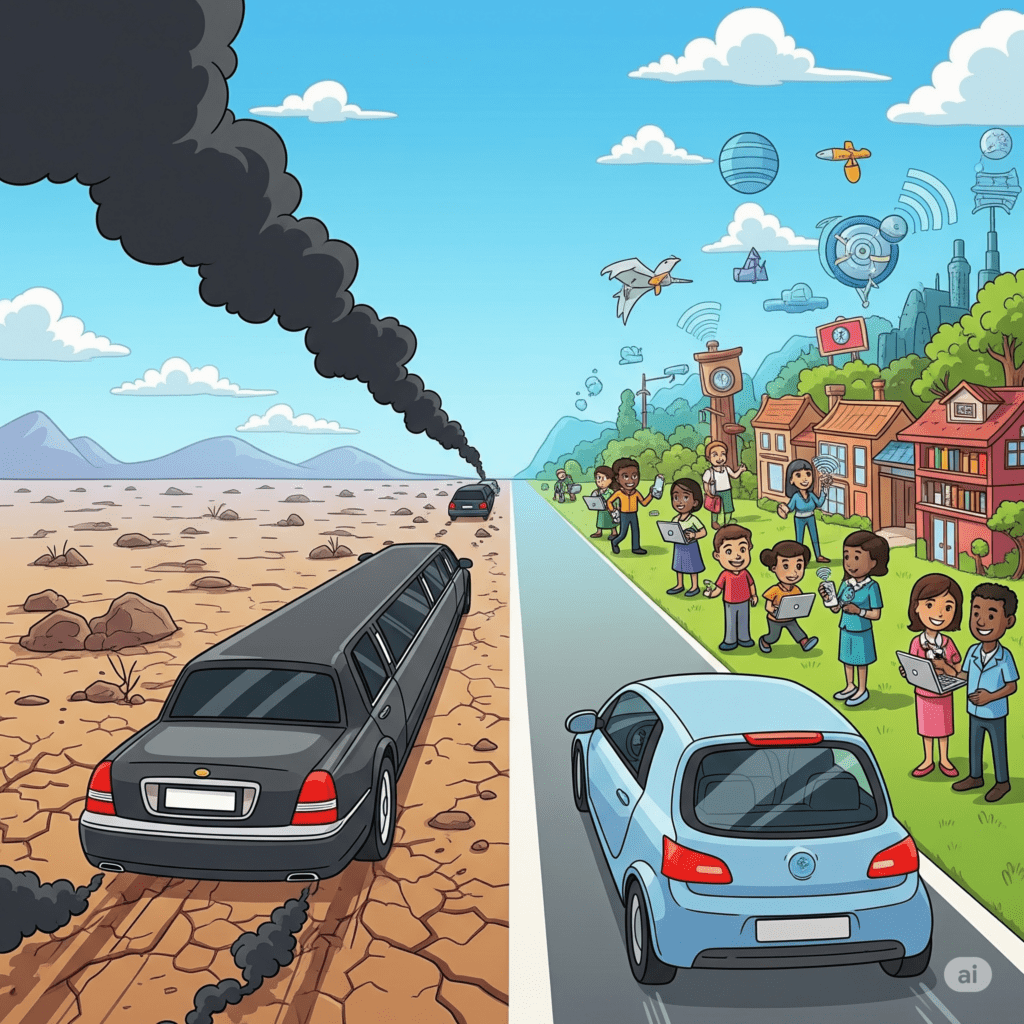

Your boss gives you a $50,000 budget for a company car. Two rules: 40+ mpg and 5-star safety. Anything you don’t spend disappears. The Honda Civic Hybrid, which costs $30k, and the Lexus ES 300h, which costs $45k, both meet the specs. Which do you choose? Obviously, the Lexus. And you might as well add the higher quality stereo and other features all the way up to the full $50k. Why forgo those extra luxuries when they don’t cost you anything?

Now imagine the same scenario, except you get to keep whatever you don’t spend. Suddenly, the price difference between the two cars matters to you. A lot. You’ve probably got better things to do with $20k.

The second scenario yields a more efficient outcome because you face an opportunity cost. Every dollar you spend on the car is a dollar you can’t spend on something else.

NTIA’s new BEAD rules just put states in scenario one with $42 billion of taxpayer money. NTIA’s MPG and safety requirements are for states to connect unconnected households at a minimum speed and latency. That part is good.

However, by eliminating states’ ability to use leftover money, NTIA has created an incentive for them to spend as much of it as possible on connections, regardless of cost-effectiveness, as long as they meet minimal criteria. In effect, NTIA is encouraging states to buy the Lexus because they’ll probably have to return unused money.

NTIA’s new rules improve the previous administration’s rules in many important ways. They eliminate requirements unrelated to broadband that resulted in making it more complicated and expensive for states to create and implement their plans. The revised rules are technology-neutral, focusing on meeting minimum quality measures rather than favoring one technology.

Those changes make it possible for states to spend the money more efficiently. But NTIA new rules then removed incentives for them to try.

States now face the prospect of losing any money they don’t spend. For example, they can’t spend money they save on digital connectivity programs and, indeed, don’t know what will happen to the leftover funds. Given that, why should states try to spend the money efficiently? They should try to spend as much money as possible in ways that benefit the state, as long as they comply with NTIA’s rules.

Consider Nevada’s experience, where some locations received over $100,000 per connection. If the new rules still allowed the state to spend leftover funds on other broadband priorities, capping costs at $20,000 would have freed up millions for those priorities. Under the new rules, those same savings are likely to vanish – so why would Nevada impose a cap?

To be clear, we’re not saying adoption programs are necessarily an efficient use of money, although they might be given that the income-based connectivity divide is larger than the geography-based divide, or that in a perfect world remaining money should not revert to the federal government.

The point is that by eliminating the ability of states to use the leftover money for anything, the rational thing for them to do is to spend as much of it as possible as long as it meets NTIA’s criteria.

One response to this argument is that NTIA has to approve plans and that imposing a cost-per-location cap ensures that funds will be spent well on a dollar-per-location measure. However, NTIA did not mandate any cap on the amount to be spent per location. It could have mandated that states set a no higher than $20,000 per location so Nevada and other states would not be spending in excess of $100,000 per location in some areas.

But regulating efficiency is, at best, difficult due to the perverse incentives regulations can create. There are always ways to comply with the letter of the rules and not the spirit, and the incentives the new rules create ensure that will happen.

Distributing these subsidies is more complicated than the hypothetical car-buying example, but the point is the same. Eliminate incentives for the states to take into account the opportunity cost of funds and they won’t spend it as efficiently as they would otherwise.

States are now at the car dealership with $42 billion, choosing between the Honda and the Lexus. NTIA has ensured that every state official should choose the Lexus. NTIA can fix this by letting states keep savings for other broadband priorities. Until then, taxpayers will pay Lexus prices when the Honda would have been just fine.

Rosston is the Gordon Cain Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research and the Director of Stanford’s Public Policy program.

Wallsten is president of the Technology Policy Institute and also a senior fellow there.

Gregory Rosston is Director of the Public Policy Program at Stanford University and Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. He is also a Lecturer in Economics and Public Policy at Stanford University where he teaches courses on competition policy and strategy, intellectual property, and writing and rhetoric. Rosston served as Deputy Chief Economist at the Federal Communications Commission working on the implementation of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 and he helped to design and implement the first ever spectrum auctions in the United States. He co-chaired the Economy, Globalization and Trade committee for the Obama campaign and was a member of the Obama transition team. He has served as a consultant to various organizations including the World Bank and the FCC, and as a board member and advisor to high technology, financial, and startup companies. Rosston received his Ph.D. in Economics from Stanford University specializing in the fields of Industrial Organization and Public Finance and his A.B. with Honors in Economics from University of California at Berkeley.

Scott Wallsten is President and Senior Fellow at the Technology Policy Institute and also a senior fellow at the Georgetown Center for Business and Public Policy. He is an economist with expertise in industrial organization and public policy, and his research focuses on competition, regulation, telecommunications, the economics of digitization, and technology policy. He was the economics director for the FCC's National Broadband Plan and has been a lecturer in Stanford University’s public policy program, director of communications policy studies and senior fellow at the Progress & Freedom Foundation, a senior fellow at the AEI – Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies and a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, an economist at The World Bank, a scholar at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, and a staff economist at the U.S. President’s Council of Economic Advisers. He holds a PhD in economics from Stanford University.