The rash of fantastical, untrue stories circulating on social media during the 2016 presidential campaign yielded the phrase “fake news” along with attempts to tackle the problem. One possible outcome of this phenomenon is people becoming more skeptical of news in general. On the one hand skepticism is healthy by making people less gullible. On the other hand, certain people exploit the problem by crying “fake news” as a response to any story or argument with which they disagree, potentially decreasing trust in reputable sources.

A rough empirical analysis suggests that people are more likely to question news when events contradict their expectations or opinions. To investigate when people may suspect news to be fake, I use Google search trend data from the 2016 presidential election. In particular, the analysis asks whether people with different political leanings tended to be more or less likely to search on Google for the phrase “fake news,” and whether those tendencies changed after the election.

I find that the higher the share of people in a state who voted for Donald Trump, the more likely they were to search for the phrase “fake news” in Google before the election and the less likely they were to search for it after the election (and vice-versa for the share of Hillary Clinton voters in a state). The results are consistent with Trump voters being more concerned about “fake news” prior to the election and Clinton voters being more concerned about it after the election. One interpretation of these results is that people are more suspicious of news when it is not consistent with their point of view.

Take this with a heaping teaspoon of salt. When I said “rough empirical analysis” above, I meant it. Consider a crucial caveat: I am assuming people mostly search for the phrase “fake news” when they are concerned about the issue. They may do that search for other reasons. I do not have information on individual voters and cannot truly know what explains the observed behavior.

Now that you’re properly warned, let’s take a look at the data.

Data

I want to measure the degree to which people are concerned about fake news. Google Trends provides a method to do that. I assume that primarily people concerned about fake news will search for the phrase.

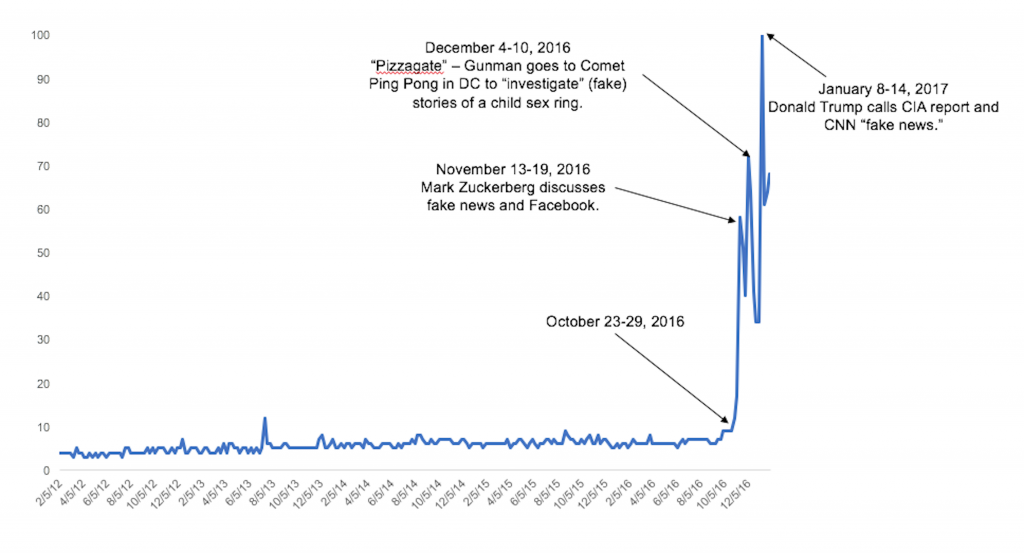

Figure 1 shows the Google Trend index for the search for “fake news” in the United States from the beginning of 2012 through February 3, 2017. The figure shows that, relative to the past few months, there were few such searches prior to November 2016. The Figure also shows spikes related to certain events. For example, on December 4, 2016 a gunman entered the Comet Ping Pong restaurant in Washington, DC to “investigate” the conspiracy stories claiming the pizza and ping-pong joint was a cover for a child sex ring run by Hillary Clinton and John Podesta.[1]

Figure 1: Google Trend Results for Search Term “Fake News” in the U.S.

Source: Google Trends. Vertical axis is an index from 0-100 showing relative popularity of the search.

Source: Google Trends. Vertical axis is an index from 0-100 showing relative popularity of the search.

Analysis

The unexpected results of the November 8, 2016 presidential election provide a natural experiment to how people’s views of “fake news” change based on expectations and actual events. Changes in Google trend data at the state level over certain periods of time demonstrate the relative interest of people in each state in “fake news” before and after the election. With data on the share of people who voted for each candidate, it becomes possible to determine whether the surprising election results changed search patterns.

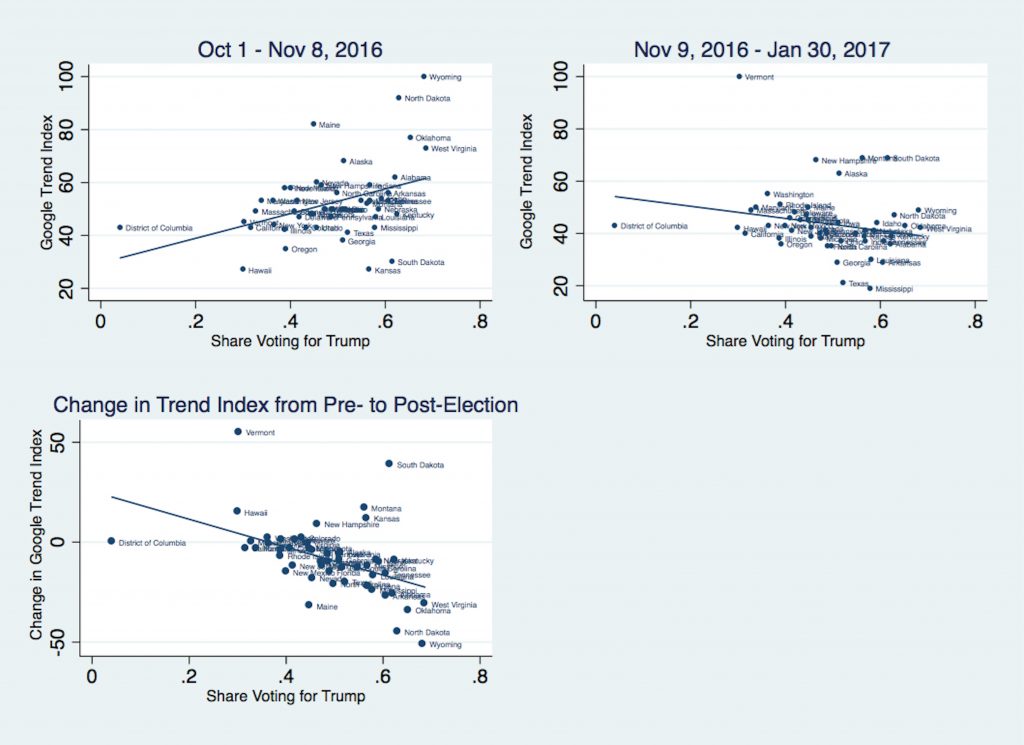

Figure 2 shows scatterplots of each state’s average Google Trend Index before and after the election and the share of voters voting for Trump, as well as the difference between the pre- and post-election indices. Because searches for “fake news” were fairly constant until October, I define the pre-election period as October 1 – November 8, and the post-election period as November 9, 2016 – January 30, 2017. The figures show that prior to the election, people in states that would vote more heavily for Trump were more likely to search for “fake news” on Google, but after the election people in states that voted more heavily for Trump were less likely to do the same search.

Figure 2: Google Trend Index for “Fake News” Search by State

Another way to evaluate the data is via a spline regression. A spline regression tests a non-linear relationship—in particular, whether the slope of the regression line changes at particular points. While a spline regression is straightforward, the setup is a bit more complicated in this context. The question is not just whether there was a change in the slope of the line after the election, but whether that change differed by the share of votes for Trump.

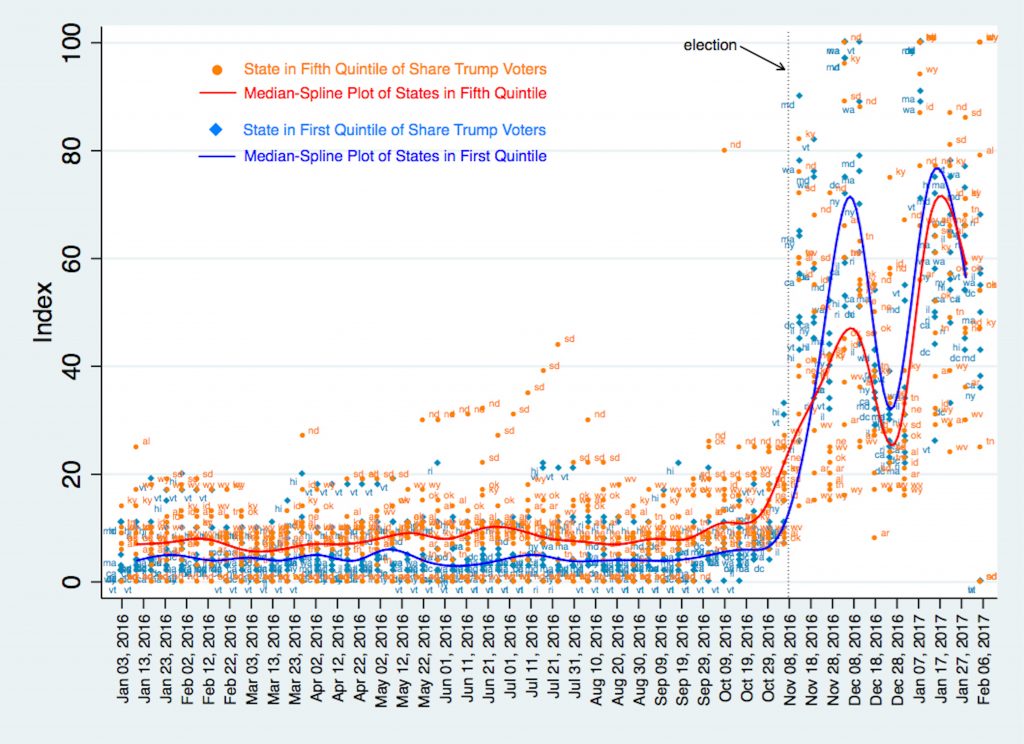

I do this by testing for a discrete change in the slope by changing the dataset so that an observation is a state-week and examining states in quintiles determined by vote share for Trump. Figure 3 shows compares the estimated median-spline curve based on states in the first quintile of Trump shares (the 10 states with the smallest shares voting for Trump) with the curve based on states in the top quintile (the 10 states that voted most heavily for Trump).

Figure 3: Median-Spline Curve of Estimated Correlation between Fake News Search Index and Trump Share of Voters

Consistent with the analysis above, the figure shows that people in Trump states tended to be more frequent searchers for the phrase “fake news” than people in Clinton states before the election, but that after the election those in Clinton states searched for the phrase more frequently. Towards the end of January 2017 the difference between the states began to narrow.

In short, the more a state would lean towards Trump in the 2016 presidential election, the more frequently its residents searched for the phrase “fake news” before the election relative to Clinton voters and the less frequently they would search for it after the election relative to Clinton voters. At a high level of generality, the results suggest Trump supporters were more likely to search for the phrase “fake news” before the election and Clinton supporters were more likely to search for it after the election.

One possible interpretation of the results is that people are more likely to be suspicious of the news when it is presenting information they do not like or with which they disagree. Thus, before the election Trump supporters were suspicious of the stories, polls, and predictions suggesting that Clinton was a shoo-in for president. After the election, surprised Clinton voters worried that fake news stories had affected the outcome.

Another interpretation is that this analysis doesn’t mean anything at all. And if that’s the case, is this blog post “fake news?”

[1] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/local/wp/2016/12/04/d-c-police-respond-to-report-of-a-man-with-a-gun-at-comet-ping-pong-restaurant/