There’s a lot to like in Hillary Clinton’s technology agenda, not the least of which is its existence. After all, Donald Trump’s tech agenda appears to include only the use of Twitter (sad!).[1] Assuming Hillary is elected we’ll surely have robust debates about the wisdom of some of the plan’s suggestions and the most effective ways to implement others.

Even though the election is still weeks away, it’s useful to look at one goal that most people share across the political spectrum: closing the digital divide, especially one based on income. Republican Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Commissioner Ajit Pai, for example, recently released his own plan intended to spur broadband infrastructure investment in low-income areas.

Given this bipartisan agreement about the goal, it’s time to think seriously about how to get there. As it turns out, we really don’t know the answer yet.

Like any normal good, where demand increases as income rise, wealthier people adopt broadband earlier and are willing (and able) to pay more for higher quality. Unlike many normal goods, as a society we hope that broadband access can help mitigate problems related to income inequality rather than being another symptom of it.

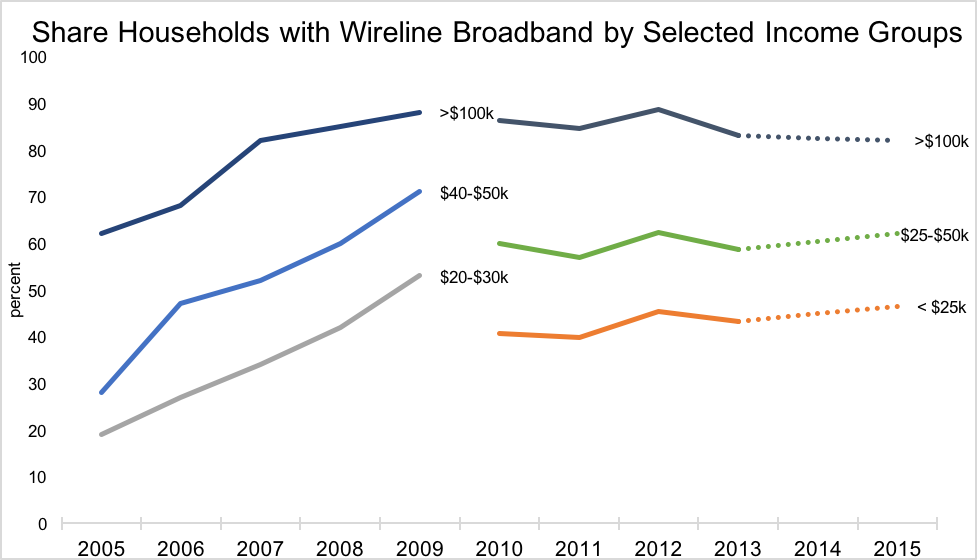

The problem is that despite the FCC’s commitment to spending $2.5 billion per year subsidizing broadband for low-income people, we simply do not know how to close this divide. Broadband subscription rates for low-income people have increased rapidly, just as they have for upper-income people, but the gap in broadband adoption across income levels has remained relatively constant (see figure below).

Sources: 2005-2009 data from Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2010-2015 from NTIA. The two sources do not always use the same income groupings. NTIA did not publish data for 2014.

Surveys conducted over the years identify a number of reasons people do not subscribe—price, relevance, and the ability to access the Internet outside of the home, to name a few. Recent FCC experiments found that very low prices did not attract many of the disconnected to sign up.

In 2013 the FCC worked with Internet Service Providers to conduct 14 separate experimental programs in order to learn how low-income people who did not then subscribe respond to different types of broadband plans, equipment options, and digital literacy training. The hope was to learn what types of subsidies and other offers would encourage low-income people without broadband to subscribe. In a recent paper I evaluated the reported results of all the projects.

The most consistent result across the programs was unexpected: extremely low consumer participation. Wireline and mobile providers (except those in Puerto Rico) managed to sign up less than 10 percent of the number of participants they had expected despite extensive outreach efforts and, in one case, a price of $1.99 per month. The pilots also revealed that the low-income people who did subscribe through one of the experimental projects tended to prefer not to take digital literacy classes. Indeed, one experiment revealed that many of the new subscribers were willing to pay an extra $10 per month to avoid mandatory digital literacy classes.

These results are difficult to interpret because they differed so dramatically from expectations. Perhaps for this reason the FCC largely ignored the pilots when it crafted its new Lifeline program, which subsidizes broadband subscriptions for low-income people. Though disappointing, it is perhaps not surprising given the FCC’s general indifference towards a long history of government evaluations and other studies demonstrating flaws, ineffectiveness, and lack of evaluation of its universal service programs.

The FCC deserves high praise for conducting those pilots and for writing an excellent analysis of them. Additionally, the inability to test rigorously many of the initial hypotheses the experiments posed does not mean the pilots failed. To the contrary, the pilots highlighted important problems in getting the last group of non-subscribers to connect.

If we wish to actually close the digital divide rather than simply spend money in order to claim that we’re closing it, then it is crucial to study the problem in more detail and not ignore results of studies we have. Why was the response rate so low, even with such low prices? Why were digital literacy classes so unpopular?

Participants’ survey responses may hint towards a possible explanation for the low response rate.

The most common answer to why they did not previously subscribe was price, but the most common reason they chose to subscribe through a pilot was to keep in touch with family and friends. Like any other consumers, they make decisions about how much they are willing to pay based on the value they get from the connection. If so, maybe policy should consider the net benefits of different types of connections rather than simply the price. (Or, perhaps not. The pilots did not test that hypothesis.)

Finding the answer matters because if broadband subsidies flow primarily to people who already subscribe then they are doing little to close the digital divide. The unexpected results of the pilot imply that the FCC should do more experiments, focused especially on ways to better attract non-subscribers.

Hillary Clinton’s and Commissioner Pai’s shared desire to close the digital divide is good. Acknowledging that we don’t yet know how and pledging to learn is the right way to start.

[1] But see ITIF’s excellent analysis of Hillary Clinton’s tech plan versus Donald Trump’s tech positions based on various statements he and his campaign have made.

Scott Wallsten is President and Senior Fellow at the Technology Policy Institute and also a senior fellow at the Georgetown Center for Business and Public Policy. He is an economist with expertise in industrial organization and public policy, and his research focuses on competition, regulation, telecommunications, the economics of digitization, and technology policy. He was the economics director for the FCC's National Broadband Plan and has been a lecturer in Stanford University’s public policy program, director of communications policy studies and senior fellow at the Progress & Freedom Foundation, a senior fellow at the AEI – Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies and a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, an economist at The World Bank, a scholar at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, and a staff economist at the U.S. President’s Council of Economic Advisers. He holds a PhD in economics from Stanford University.