Wireless data pricing has been evolving almost as rapidly as new wireless devices are entering the marketplace. The FCC has mostly sat on the sidelines, watching developments but not intervening.

Mostly.

Last summer, the FCC decided that Verizon was violating the open access rules of the 700 MHz spectrum licenses it purchased in 2008 by charging customers an additional $20 per month to tether their smartphones to other devices. Verizon paid the fine and allowed tethering on all new data plans.[1]

Much digital ink has been spilled regarding how to choose a shared data plan best-tailored for families with a myriad of wireless devices and demand for data. Very little, however, appears to have been said about individual plans and, more specifically, about those targeted to light users.

One change that has gone largely unnoticed is that Verizon effectively abandoned the post-paid market for light users after the FCC decision.

Verizon no longer offers individual plans. Even consumers with only a single smartphone must purchase a shared data plan. That’s sensible from Verizon’s perspective since mandatory tethering means that Verizon effectively cannot enforce a single-user contract. The result is that Verizon no longer directly competes for light users.

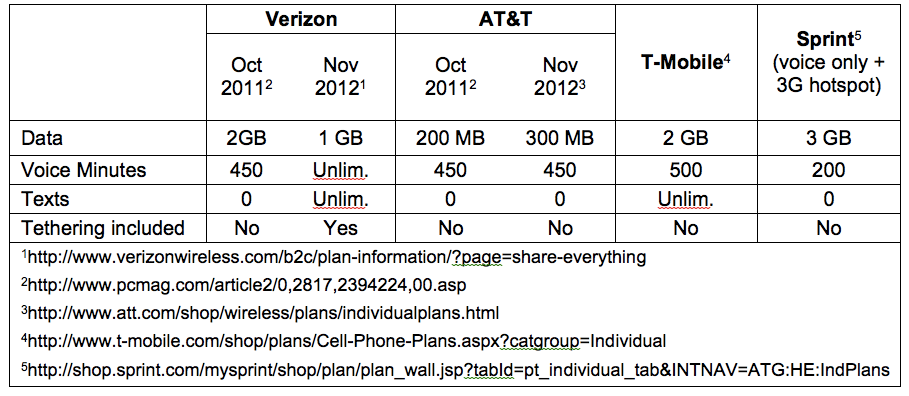

The figure below shows the least amount of money a consumer can pay each month on a contract at the major wireless providers. As the table below the figure highlights, the figure does not present an apples-to-apples comparison, but that’s not the point—the point is to show the choices facing a user who wants voice and data, but the smallest possible amount of each.

Note: Assumes no data overages.

The figure shows that this thrifty consumer could spend $90/month at Verizon, $60/month at AT&T, $70/month at T-Mobile, and $65/month at Sprint if the consumer is willing to purchase voice/text and data plans separately. Even Verizon’s prepaid plan, at $80/month, costs more than the others’ cheapest postpaid plans.

Moreover, prior to the shift to “share everything” plans, this consumer could have purchased an individual plan from Verizon for $70/month—$20/month less than he could today. At AT&T the price was $55/month but increased by only $5/month. Again, the point is not to show that one plan is better than another. Verizon’s cheapest plan offers 2 GB of data, unlimited voice and texts, and tethering while AT&T’s cheapest plan offers 300 MB of data, 450 voice minutes, and no texts or tethering. Which plan is “better” depends on the consumer’s preferences. Instead, the point is to show the smallest amount of money a light user could spend on a postpaid plan at different carriers, and that comparison reveals that Verizon’s cheapest option is significantly more expensive than other post-paid options and, moreover, increased significantly with the introduction of the shared plan.

Is the FCC’s Verizon Tethering Decision Responsible for this Industry Price Structure?

There’s no way to know for sure. The rapidly increasing ubiquity of households with multiple wireless device means that shared data plans were probably inevitable. And carriers compete on a range of criteria other than just price, including network size, network quality, and handset availability, to name a few.

Nevertheless, Verizon introduced its “share everything” plans about a month before the FCC’s decision. If we make the not-so-controversial assumption that Verizon knew it would be required to allow “free” tethering before the decision was made public and that individual plans would no longer be realistic for it, then the timing supports the assertion that “share everything” was, at least in part, a response to the rule.

How Many Customers Use These “Light” Plans?

Cisco estimated that in 2011 the average North American mobile connection “generated” 324 megabytes. The average for 2012 will almost surely be higher and even higher among those with higher-end phones. Regardless, even average use close to 1 Gb would imply a large number of consumers who could benefit from buying light-use plans, regardless of whether they do.

Did the FCC’s Tethering Decision Benefit or Harm Consumers?

It probably did both.

The consumer benefits: First, Verizon customers who want to tether their devices can do so without an extra charge. Second, AT&T and Sprint followed Verizon in offering shared data plans, with AT&T’s shared plans also including tethering. Craig Moffett of Alliance Bernstein noted recently that “Family Share plans are not, as has often been characterized, price increases. They are price cuts…”[2] because the plans allow consumers to allocate their data more efficiently. As a result, he notes, these plans should cause investors to worry that the plans will reduce revenues. In other words, the shared plans on balance probably represent a shift from producer to consumer surplus.

The consumer costs: Verizon is no longer priced competitively for light users.

The balance: Given that other carriers still offer postpaid plans to light users and that a plethora of prepaid and other non-contract options exist for light users, the harm to consumers from Verizon’s exit is probably small, while the benefits to consumers may be nontrivial. In other words, the net effect was most likely a net benefit to consumers.

What Does This Experience Tell Us?

The FCC’s decision and industry reaction should serve as a gentle reminder to those who tend to favor regulatory intervention: even the smallest interventions can have unintended ripple effects. Rare indeed is the rule that affects only the firm and activity targeted and nothing else. More specifically, rules that especially help the technorati—those at the high end of the digital food chain—may hurt those at the other end of the spectrum.

But those who tend to oppose regulatory intervention should also take note: not all unintended consequences are disastrous, and some might even be beneficial.

Is That a Unique Observation?

Not really.

Could I Have Done Something Better With My Time Instead of Reading This?

Maybe. Read this paper to find out.

[1] The FCC allowed Verizon to continue charging customers with grandfathered “unlimited” data plans an additional fee for tethering.

[2] Moffett, Craig. The Perfect Storm. Weekend Media Blast. AllianceBernstein, November 2, 2012.